Contents

PART 1

About Liudzi

Learn about the purposes and goals of the project.

PART 2

A Note on the Languages Used in Belarus

Useful information for navigating the text.

PART 3

Profile: Alexander Lukashenko

Information of Alexander Lukashenko, self-declared president of Belarus

PART 4

Profile: Svetlana Tikhanovskaya

Information on the head of Lukashenko's opposition.

PART 5

Election & Aftermath

The events surrounding the August presidential election.

PART 6

Continuing Efforts

The efforts by the Belarusian opposition to demand liberty into fall and the new year.

PART 7

Actions of the Belarusian Police

The atrocities committed by the Belarusian Police Force at the orders of Lukashenko.

PART 8

First-Hand Experience: A Belarusian's Thoughts

An interview with a Belarusian who has lived through the described events.

PART 9

World Reaction and Parallels

What's going on in the rest of the world in relation to the events of Belarus.

“Belarus is an authoritarian state.

The constitution provides for a directly elected president who is head of state and a bicameral parliament, the National Assembly.

A prime minister appointed by the president is the nominal head of government, but power is concentrated in the presidency, both in fact and in law.

Citizens were unable to choose their government through free and fair elections.

Since his election as president in 1994, Alyaksandr Lukashenka has consolidated his rule over all institutions and undermined the rule of law through authoritarian means, including manipulated elections and arbitrary decrees.

All subsequent presidential elections fell well short of international standards.”1

— U.S. Department of State, 2019

About Liudzi

MAP OF BELARUS.

Liudzi (lood-zee) is a project dedicated to spreading information about the current human rights crisis in Belarus. Since a contested presidential election in August 2020, Belarus has been embroiled by a conflict between authoritarian leader Alexander Lukashenko and the Belarusian public. Lukashenko, a politician with a history of rigged elections, claims that he won the 2020 election by a large margin, while his opponent, Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, maintains the opposite. Since then, regular, largely peaceful, protesting has occurred throughout the country, often facing excessive and brutal backlash from the Belarusian police force. Liudzi’s mission is to educate an American audience about an issue which receives limited exposure in the United States. While it may seem like a distant struggle, many of those opposing Lukashenko, including Tikhanovskaya herself, are looking to the United States, along with other nations, for assistance in winning their battle. The United States government needs the American public’s support in taking a firm stance against the atrocities committed by Lukashenko and his regime and ensuring Belarus is able to achieve a true democracy.

Links to sources are provided in-text, just click the footnote number to open the source in a new tab. Additionally, the full list of sources is listed in the bibliography at the bottom of the page. Please note that this is an ongoing event. The information in this essay only extends into early April 2021, but, at the time of writing, there has yet to be a resolution; the savagery being committed by the Belarusian government continues.

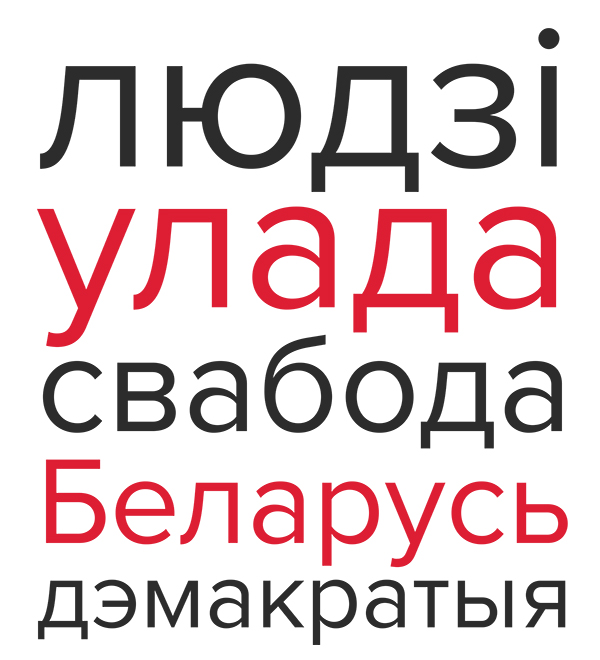

A Note on Languages Used in Belarus

BELARUSIAN WORDS IN THE CYRLLIC ALPHABET.

Belarus’s unique history has made it a multilingual state. Throughout much of its history, Belarus lacked an independent identity, the area instead was part of other larger European countries. The land of Belarus eventually ended up under the control of the Russian Empire, during which time the growth of Belarusian culture, including its language, was stunted.2 While there was some effort to further develop the Belarusian culture in the early 20th century, Russian still remained the most prominent language.3 In recent decades, the Belarusian language has seen a resurgence; it is now recognized as an official language alongside Russian. Due to this, people and places will often have two different names, one in Russian and one in Belarusian. Throughout this essay, the English transliterations of the Russian names will be used as the preferred version. This is not done for any politically-driven reason, but simply to help with recognition for an English-speaking audience.

Profile

Alexander Lukashenko

Alyaksandr Lukashenka

SELF-PROCLAIMED PRESIDENT OF BELARUS

Alexander Lukashenko rose to power in 1994, shortly after Belarus gained its independence from the Soviet Union. The years immediately following the independence of Belarus were marked with economic turmoil, so Lukashenko won over the public by promising a return to the way things were before the Union’s dismantlement.5 Lukashenko struck a deal with the Russian government, securing affordable power supplies for the energy-dependent nation and helping to improve living standards throughout the country.6 Lukashenko used this success as a way to win over more voters—and he was successful. Even down in the line, facing declining relations with Russia in the mid-2000s, opinion polls suggested that Lukashenko was still generally favored by the Belarusian public.7

Despite his initial popularity, Lukashenko was quick to take advantage of the power that he had. In 1996, following a referendum, the Belarusian parliament was dissolved, instead replaced by a body that was easily manipulated by Lukashenko.9 This same referendum gave Lukashenko power over many key organizations throughout Belarus. Six years later, term limits were removed from the position of president, allowing him to reign over the fledgling nation indefinitely.10 It is evident through all these changes that Lukashenko was eager to hold as much control over his country and his people as possible, no matter what.

In regard to Russia, he consistently avoided making good on any of his side of their agreements,11 but managed to stay in their good graces through several methods. He touted himself as the last true ally of the once-great state and even suggested that he would like to create a joint state with Russia, reuniting the countries as in Soviet times.12 Through the years, opinions of Lukashenko began to decline both internally and externally. On an international level, following reports of human rights violations, he faced sanctions from European and American governments.13 Internally, protests were held against him, such as after the 2010 election, where official government reports indicated that Lukashenko had won by a landslide. Other reports suggested he won barely half the votes.14 This would prove to be a pattern for Lukashenko, as we will see moving into the events of 2020. More recently, Lukashenko has downplayed the risks of coronavirus, refusing to take it seriously even in spite of contracting it himself.15

Profile

PORTRAIT OF SVETLANA TIKHANOVSKAYA,

BASED ON PHOTOS BY BUNDESMINISTERIUM FÜR EUROPÄISCHE UND INTERNATIONALE ANGELEGENHEITEN.16

Svetlana Tikhanovskaya

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya

LEADER OF THE BELARUSIAN OPPOSITION

Svetlana Tikhanovskaya was a low-profile figure until shortly before the 2020 election. A housewife and mother, she wasn't on the radar as any sort of political opponent for Lukashenko. This changed in May 2020, when Tikhanovskaya’s husband Sergei Tikhanovsky was arrested. Tikhanovsky, a blogger that announced he would run against Lukashenko in the elections, was taken into police custody for being part of “unsanctioned public gatherings.” 17 Refusing to let the arrest of her husband be in vain, Tikhanovskaya took it upon herself to run in his place. She said that when she first signed up to run for the election, she wasn’t thinking so much about her country, stating “Maybe it sounds wrong. But [...] I was thinking only about my husband, to support him.” 18

While it may not have been her initial intention, Tikhanovskaya became a figurehead for the opposition of Lukashenko. She was not a political woman, but she made it her mission to remove Lukashenko as president. Discussing Tikhanovskaya’s plan, Sarah Rainsford, journalist for BBC News, wrote, “The women [Tikhanovskaya and her team] have no political programme, just one plea: vote for Svetlana to oust Mr Lukashenko then she'll call fresh, fair elections and free all the political prisoners.” 20 Tikhanovskaya’s team quickly gained support from large portions of the Belarusian public, a group who was tired of Lukashenko's rigged elections and firm grip on power. Many younger voters at this point had spent their whole life living under Lukashenko’s rule, so it’s not surprising that there was an increased demand for change. As Tikhanovskaya’s campaign gained momentum, it became unclear what the results would be moving into the month of the election.

Election & Aftermath

Tensions were high entering August. In the months leading up to the election, other candidates who were opposing Lukashenko had been arrested and barred from participation.21 According to international organization Human Rights Watch, “The presidential elections were marred by arrests of leading opposition candidates, groundless refusals to register certain opposition candidates for the ballot, and allegations of widespread fraud.” 22 This was part of Lukashenko’s attempts to quell any sort of contest for the election, which led to Tikhanovskaya being his only threat. Peaceful protests had occurred across the country over the summer, leaving hundreds detained by the police.23 Tikhanovskaya had been forced to evacuate her children from the country after anonymous threats due to her election bid brought their safety into question.24 Things were heating up as the election approached ever nearer. After months of unease, August 9, the date of the election, promised to bring release—a respite from the storm that had been brewing in the country. Unfortunately, a peaceful election was not in the cards for Belarus.

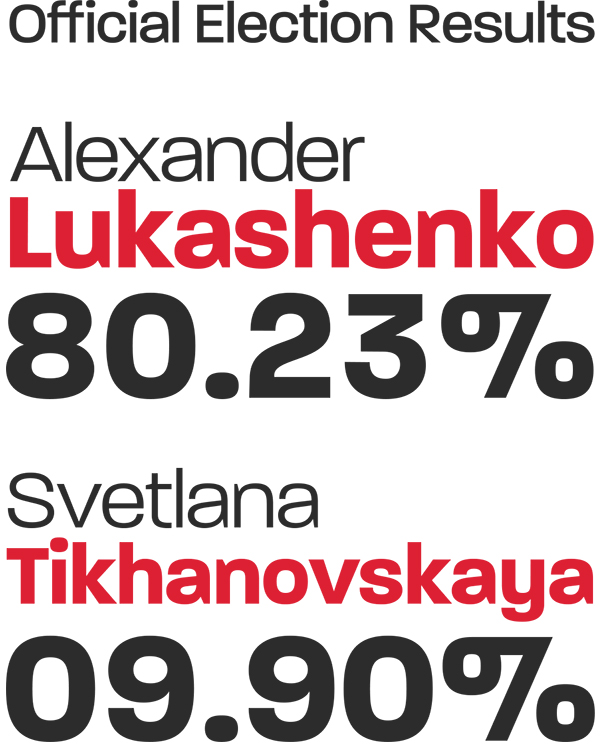

BASED ON DATA FROM CNN.25

As Belarusians streamed out to polling locations that Sunday morning, nobody could have known what would be coming. Ballots were counted without observance from any independent parties and polling locations were quick to announce the results, with Lukashenko being declared as the projected winner by the end of the night, granting him over 80% of the vote and Tikhanovskaya just under 10% (meanwhile, reports by other groups put forth that Tikhanovskaya had in fact received a much larger share of the votes, a number closer to the 80% that Lukashenko claimed for himself).26 Outrage ensued. Tikhanovskaya’s supporters felt they had been duped, insisting the election had been rigged (an act that would not be out of the question for Lukashenko). Protests erupted in the capital of Minsk and other cities around Belarus. The people rushed to the streets en masse, throngs of protesters numbered in the tens of thousands rushed to express their discontent. While this began, Tikhanovskaya herself had to flee the country,27 becoming a leader-in-exile for the opposition.

In the days immediately following the election, the protesters (almost all of whom were peaceful) were met with severe repression from authorities, facing “stun grenades, rubber bullets and slugs, blanks from Kalashnikov-type rifles, and tear gas.” 28 The police cracked down on the protesters with excessive force, turning what would have been a peaceful cry for justice into a whirlwind of chaos. At the same time, an Internet blackout engulfed the country. The blackout, claimed by Lukashenko’s government to have been caused by foreign interference,29 left many in the dark in regards to what was happening throughout Belarus. The one platform that seemed resistant to this blackout was the Russian social media network Telegram. Thanks to special-designed software meant to withstand such obstructions, Belarusians were able to use Telegram to continue communicating.30 Many flocked to one specific group of channels, those run by Nexta. According to the Financial Times, “After the election, its [Nexta’s] subscriber base surged to 2.17 million — more than a fifth of Belarus’s 9.5 million population.” 31 Up to this point, Nexta had functioned mainly as a journalism platform, but it was soon transformed into something much more. Because other forms of communication had been hampered, Nexta quickly became not only a place to share photos and videos from the streets of Belarus, but a central hub from which protests were able to be organized—a role which it would continue to fill in months to come.32 During these few days immediately following the election, it’s estimated that approximately 7,000 people were detained (both protesters and non-protesters alike, seemingly without distinction) and several had been killed.33 This ruthless display of force did little to deter the protesters. In fact, it emblazoned them to continue their efforts. On August 23, a massive rally was held in the center of Minsk. According to BBC News, “Pro-opposition media say 100,000 people took part. State television put the crowd at 20,000.” 34 In the coming weeks, protests would continue as the struggle raged on in Belarus.

Continuing Efforts

A GIRL STANDS ALONE HOLDING THE FLAG OF THE BELARUSIAN OPPOSITION,

BASED ON A PHOTO BY ILYA KUZNIATSOU.35

Both sides kept trying to assert their dominance as summer turned to fall and the cool autumn air chilled Belarus. Lukashenko continued to insist he was the rightful leader. On September 23, in spite of continued opposition, he was sworn in during a secret inauguration. “The inauguration had not been announced,” stated NPR’s Lucian Kim, describing the ceremony. “And there were no foreign delegations, not even from Russia, Lukashenko's strongest backer.”36 The sneaky nature of the event fell in line with the general attitude of Lukashenko’s government at the time. However, governments around the world continued to deny recognizing Lukashenko’s election result. The following day, the Council of the European Union released a statement on the matter, saying, “The 9 August Belarus Presidential elections were neither free nor fair. The European Union does not recognise their falsified results. On this basis, the so-called ‘inauguration’ of 23 September 2020 [...] [lacks] any democratic legitimacy.” 37 Meanwhile, the Belarusian authorities continued to violently suppress opposition protesters. By early October, the Belarusian government informed authorities that they were permitted “to use lethal force”38 against protesters. They villainized the protesters, saying “The move was in response to increasingly radicalised, violent anti-Lukashenko groups,” 39 even though the vast majority of protests following the election had been peaceful. A series of graphs from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project show that in all the protests that took place leading up to the election and going into September, only a sliver featured violent demonstrations,40 rebutting the accusations of the Belarusian government.

Even facing increasing threat from the police force, the Belarusian people were resilient. Protests continued to remain frequent, occurring every week to continue supporting the opposition’s cause. Tikhanovskaya continued acting as a leader for the opposition despite being exiled to Lithuania, helping to guide protesters in their battle against Lukashenko. On October 13, she announced “the people’s ultimatum,” which consisted of three demands: Lukashenko’s resignation, the ending of violence against protesters, and the release of political prisoners. She gave a deadline of October 25 and declared that, if Lukashenko didn’t meet these demands, a nationwide strike would take place.41 Not surprisingly, given the government's previous actions, they did not comply with Tikhanovskaya’s demands. The strike was held on October 26, bringing students out of classrooms, workers out of factories, and pensioners out to the streets.42 The groups marched together, but it didn’t bring the infrastructure of Belarus to a halt. The ultimatum had failed to yield results, yet the people of Belarus marched on. They agreed with what Tikhanovskaya wanted, as can be seen in a survey conducted in late 2020, which shows the demands of the ultimatum listed as three of the top four reasons for having participated in protests, along with the desire for a new, fair election.43

BASED ON INFORMATION FROM BBC NEWS.44

In November, another harsh blow ignited a flame in the protesters. On November 12, a teacher and veteran, Roman Bondarenko, died in a coma after a confrontation with authorities the night before. Bondarenko was beaten by a group of “plainclothes police officers [...] in a dispute over ribbons indicating support for anti-government protests,” during which he hit his head and was whisked away by the officers, only to turn up in the hospital the following day.45 While protesters faced constant physical threat from the police throughout the demonstrations, deaths attributed to them were rare, making Bondarenko’s case particularly noteworthy. The following day, Tikhanovskaya called for stronger actions on the part of the protesters. A report from the Institute for the Study of War stated that “Tikhanouskaya [sic] called on Belarusians to physically capture Lukashenko, regime officials, and security forces responsible for carrying out Lukashenko’s orders so they can stand trial at an upcoming ‘People’s Tribunal.’ ” 46 This marked the first time that Tikhanovskaya had suggested violence on the part of the protesters in place of peaceful demonstrations, indicating the escalation in tensions that Bondarenko’s death caused.

Freezing temperatures and snowstorms brought protests to a crawl as winter set in, reducing the size and frequency of demonstrations. Even still, Lukashenko couldn’t avoid the scandal that surrounded him. Leaked audio from a meeting that took place almost a decade before suddenly came to light. The recording, within which voices of high-ranking members of Lukashenko’s KGB can be heard, had discussions of secretly assassinating various people that were causing trouble for the government, including one journalist who later died in a car-bombing incident that as of then had been unsolved.47 This acted as further evidence of the corruption that shrouded Lukashenko’s government and made his position dangerous. On the flip side, the same week that this audio came out, Lukashenko declared that 2021 would be known in Belarus as “the Year of People's Unity” 48 in an attempt to quell the anger of the opposition and make himself appear benevolent. He maintained that the protests were misguided, saying, “If you dislike your current president, only elections can resolve this issue.” 49 This statement failed to take into account the dishonest nature of the presidential elections in Belarus. Continuing with his charade of his role as a kind leader, Lukashenko announced that he would plan to go ahead with a constitutional reform, an action which the Russian government had been pressuring him into for months. The suggestion was that, following the reform, Lukashenko would remove himself from office. However, after announcing that it could be over a year before such a reform occurred, it seemed likely that it was just a way to delay any real change.50

Despite Lukashenko’s suggestion of unity, the government continued to come down hard on the protesters. A January article from Russian news source TASS stated that “more than 33,000 people were detained in the country in 2020 for taking part in peaceful rallies and over 900 criminal cases were launched.” 51 Included in this number was the detainment of almost 500 journalists,52 who, as we will see, soon became Lukashenko’s next targets. “Belarusian law enforcement officials carried out a nationwide wave of raids targeting human rights defenders and journalists on February 16, 2021, rounding up at least 40 people and searching their homes and offices,” 53 reported Human Rights Watch. This unethical, oppressive action against freedom of information that is so indicative of Lukashenko’s regime garnered attention from media worldwide, especially when two journalists were dealt prison sentences shortly after for reporting on a protest.54

On March 25, anniversary of the independence of the Belarusian People’s Republic in 1918, the long-awaited reignition of protesting was restrained by Lukashenko’s government. Tikhanovskaya called for a demonstration to take place in a square in Minsk, however the police force, also aware of this, prepared by positioning themselves at the square and shutting down surrounding roads. Despite no large-scale protest occurring, a large number of Belarusians were detained, a number around 200, according to the Moscow Times.55 This muffled start to the season, which was expected to help topple Lukashenko, was also marked with a split in the opposition. Other members of the opposition, Pavel Latushko and Viktor Babariko, made the decision to form their own political parties, despite Tikhanovskaya’s de facto leadership of the group.56 This divide, coupled with a series of proposed law amendments that would severely constrict the ability of journalists to cover any protests without legal repercussions,57 brought an air of uncertainty to the future of the movement. At the time of writing, these are the most recent events surrounding the protests in Belarus, but the situation is continuing to evolve, so refer to reliable news outlets for current information on what is going on.

Actions of the Belarusian Police

As has been brought up multiple times throughout this essay, the appalling actions committed by the Belarusian police against those who were peacefully protesting has created some of the greatest tension and most horrific moments of the demonstrations. As of early April 2021, Reuters stated, “Over 34,000 people have been detained since the start of regular demonstrations in August.” 59 As has been mentioned earlier in this essay, this statistic covers both protesters and non-protesters alike, including journalists. This staggering number helps to demonstrate the scale of the impact the police force has had on the protests.

Before and after the police were granted the authority to use lethal weapons in October,60 demonstrators were constantly threatened by the excessive force employed by them. The “rubber bullets, stun grenades, and tear gas” 61 reported by Human Rights Watch, as well the use of water cannons reported by BBC News,62 mark just some of the dangers presented by the authorities. While these posed threats during the large gatherings, many of the worst repercussions were faced by those who were caught. Harassment, beatings, or worse could await any protester who found themselves in close contact with or detained by the police. Human Rights Watch stated, “Former detainees described beatings, prolonged stress positions, electric shocks, and in at least one case, rape. Some had serious injuries, including broken bones, skin wounds, electrical burns, or mild traumatic brain injuries.” 63 These disturbing reports paint a gruesome picture of what occurred after Belarusians were randomly pulled off the streets by the police force. Accusations also arouse that the police began using a color-coded system to decide how detained protesters would be treated, spray painting on their clothing to represent what type of torture they should endure.64 There was even a handful of detainees who came forward to state that they had been sent to some form of internment camp for a short time,65 though there is limited evidence to support these claims.

In spite of all these atrocities unleashed upon the Belarusian public by the police force, no action was taken against them by the courts. In late January, human rights organization Amnesty International wrote that of the “more than 900 complaints of abuses committed by police since demonstrations began in August 2020, not one criminal investigation has been launched against law enforcement officers.” 69 On the contrary, the only legal action being executed was against the protesters and anyone who posed any sort of threat to Lukashenko’s regime. As the TASS article quoted in the last section noted, nearly a thousand criminal cases had been launched against protesters as of January.70 A statement released by the United Nations the following month declared that “nearly 250 people have received prison sentences on allegedly politically-motivated charges in the context of the 2020 presidential election.” 71 This way of fear mongering has been used as a method by the Belarusian police and judicial system to inhibit protesters from continuing to demand a fair election and to make their situation feel hopeless. The targeting of journalists by the authorities, discussed in the previous section, which continued into the winter also supported this goal. At the moment, it is unclear whether those who have faced brutality at the hands of the Belarusian police in the wake of the 2020 election will ever see justice served.

First-Hand Experience: A Belarusian's Thoughts

![A close-up illustration of [REDACTED]'s eyes](img/redacted.jpg)

CLOSE-UP OF [REDACTED]

The following section was created from a digital interview conducted with a Belarusian university student, [REDACTED]. All text from this section is either quoted or paraphrased from [REDACTED] and therefore represents his thoughts and opinions as someone who has spent his life in Belarus and seen first-hand the events that unfolded in Minsk. Note that some punctuation has been altered in quoted passages in this section for the sake of clarity.

“I was fucking shocked.” These were the first words [REDACTED] had to say about what he saw after the election. “I lived with Lukashenko my whole life and it was always very [politically] stable here,” he said, noting that Lukashenko presents himself as “a big father who saves us from evil Western occupants who want to make slaves from us.” “Stability” is Lukashenko’s “favorite word,” he said, in reference to Lukashenko’s façade of maintaining a stable country. Returning to discussing the election times, he expressed his disbelief in what he saw in “ ‘stable’ Belarus.” He had gone out to give his aunt a ride home from work, but what he encountered was far from what he expected. He described soldiers “with machine guns, running at peaceful demonstrators.” The demonstrators, he said, had gone out to contest Lukashenko’s claim of victory, but they were faced with fierce retaliation. Before his eyes, he saw protesters who had been injured during the demonstration as they struggled to escape, wounded and bloodied. “This day was the deciding day,” he said, “because we [the people of Belarus] understood how many of us there are and how tired we are from that dictator.” The “silent agreement” that the people of Belarus maintained had disappeared, to be replaced instead by hatred. There is talk that, in different circumstances, the Belarusian people would have been able to achieve a swift victory, [REDACTED] reported. “If they didn't turn off the internet everywhere in the country—everybody would see what happened these first 3 days and literally everybody would go on the streets—but it was summer, and many people didn't even know what happened because they were outside big cities.”

Despite his disappointment in the election results, [REDACTED] wasn’t surprised by them. When discussing his feelings regarding the results, [REDACTED] claimed: “Everybody here knows how he [Lukashenko] ‘collects’ voices: for example, every state employee [...], every worker of any ministry and any administrational organisation, and many, many other ‘prisoners’ MUST vote for Lukashenko.” He asserted that this alone wouldn’t be enough to skew the vote, but rather that it was a “protective measure” to make it so fewer votes would need to be falsified. This was a recurring theme in Belarusian elections, a fact that was well known but which nothing could be done about. Over time, the elections began to face some opposition, but never anything significant because of the way dissidents were punished. [REDACTED] described the Belarusian government as a “big mafia of countryside rednecks who got the power.” To move up in the world of Belarusian politics, he stated, “you are to lick Lukashenko's ass, to be the obedient boy, to agree totally with the governmental policy. You must help Lukashenko to stay in his place endlessly, and then you get some privileges. You must be his wallet who helps him to wash out illegally wasted money from Belarus.” However, Lukashenko did make attempts to obfuscate his own corruption by rounding up other officials to prosecute for acts of corruption. “You must understand how ridiculous it looks,” [REDACTED] said. “Some from them [the prosecuted officials] conflicted with Lukashenko, some from them denied to pay Lukashenko, some were just a pawn for bigger guys who stole and keep on stealing Belarusian money.” Thus was the way in which Belarusian elections usually unfolded. However, [REDACTED] noted that this time it was different. Thanks to increased coverage online of other candidates, it made it more difficult for Lukashenko to maintain his act, even despite his efforts to bar others from running.

Talking more about Lukashenko’s more recent actions, [REDACTED] made it clear that he adamantly opposes what he and his regime have done. “There is no other way of understanding [...] [their] actions except full non-acceptance.” He said that you only have to “dive into the ocean of constant lies” perpetuated by the government to get a sense of their maliciousness. He discussed the protesters who had been tortured and beaten by the police, sometimes to the point of death (such as in the case of Roman Bondarenko). Continuing this line of thought, [REDACTED] went on to talk about the “many, many young girls [...] who were raped” by members of the Belarusian police force and he warned that, for many young Belarusian women who found themselves confronted by the police, they were lucky if they were only subjected to groping and harassment. “And that is only a tiny part of that huge list of terrible crimes to be investigated,” he said, then posed the question: “But what ‘crimes’ are really investigated now?” According to [REDACTED], the authorities were coming out of the situation clean. Rather than the police, the consequences fell instead on the protesters. “Peaceful demonstrators who were arrested and then beaten, and so on, then often have to confess to crimes they didn't do.” He talked about the way in which people who had done nothing wrong or only done something mild, like graffitiing a sidewalk, would end up facing harsh legal repercussions. “Instead of investigating the continuing violence cases, they just spend all their forces to fight the non-conformity.”

When asked about his thoughts on Lukashenko’s moniker of “Europe’s last dictator,” [REDACTED]’s response was clear: “Lukashenko was never an actual president,” but rather he has been “a dictator since 1994,” the year of his initial election. [REDACTED] criticized the way Lukashenko snuffed out any of the democratic ideas that had begun to form following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, putting in place instead his own autocratic regime. Most people who had anything against Lukashenko “were just shut up,” he said, while “the most active opposition leaders were killed.” He noted the manner in which the parliament was dissolved in the ’90s to be replaced by a more malleable body. “It was the beginning of his total control of everything here,” [REDACTED] said, because the replacement for the parliament was nothing more than a group who did “everything he [Lukashenko] told them to do.”

[REDACTED] was quick to note that the Belarusian authorities had been “strongly prepared” to face protesters after the election. He suggested that the heads of these forces were aware that Lukashenko would attempt to rig the election once more, therefore they had taken measures to ensure their officers would be ready. [REDACTED] stated that he believes the authorities were pumped full of anti-opposition propaganda leading up to the election. The “best tactic of a typical dictator is to tell to people that there are enemies all around us,” he said. He continued by giving examples of the types of propaganda the Belarusian government pushes out: There are “no American tanks here only because he is such a wise ruler and he saves us all, and that's why we should further support them.” Building off of the comment about American tanks, he noted that the Belarusian government treats the United States as “the main enemy in the world.”

When he was describing the protests themselves, [REDACTED] wanted to emphasize the pacifist nature of the protests. “Our history of protests is special,” he said. “We don't like to use the language of force,” something which he contrasted against the aggressive nature of the authorities, whom he referred to as “Lukashenko’s robots.” He conceded that there are certain situations where this kind of protesting isn’t effective, such as in the case of the violent ongoing conflict in Hong Kong, “but that is our, Belarusian, way,” he remarked. “Not only because of our national traits, also because of many circumstances,” such as Lukashenko’s fear of such protests, which he extrapolated from the way the president had greatly increased the domestic armed forces of the country to help control demonstrations. [REDACTED] described his own experience visiting the protests, where he was forced to flee to escape police officers for fear of being subjected to the same punishments faced by others who had been captured.

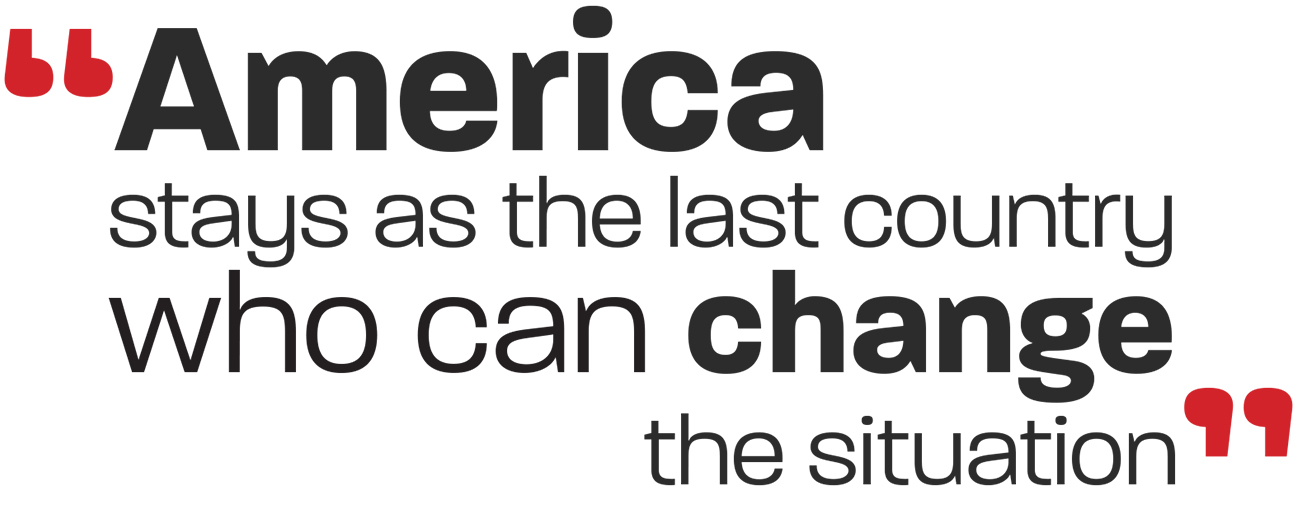

On the topic of foreign involvement, [REDACTED] was firm with his opinion: The United States needs to become more involved. It’s “time to act decisively,” he said, because “Russia is controlled by Putin's team, who still is the main reason why Lukashenko is still where he is. So, America stays as the last country who can change the situation.” [REDACTED] encouraged the United States to not only take on a more active role in opposition to Lukashenko, but also to think about the Belarusian citizens. He suggested even opening up some sort of program for Belarusians who desire to emigrate from the country in its time of crisis. “I understand US can't host many people, but make a foundation, make a competition, [...] make a commission.” Right now, foreign involvement is sorely lacking in favor of the opposition, but it’s necessary to turn the tables.72

World Reaction and Parallels

Since the 2020 Belarusian election took place, there have been various responses from governments around the world. Some countries, including Russia and many other former Soviet nations, were quick to congratulate Lukashenko on his “victory” in the election,73 affirming their stance that they did not believe the election to be fraudulent. Belarus continued to partake in joint military exercises with many of those nations 74 and Russia actively supported Lukashenko against the protesters, even offering to send in military support.75 Given Russia’s history with Belarus and their own politics, it’s no surprise that they would side with Lukashenko’s regime and choose to assist him against what could lead to a more democratic, and more Westernized, Belarus. However, despite Russia siding with the Belarusian government over the protesters, they are also the ones who pressured Lukashenko into agreeing to a constitutional rewrite and change of leadership,76 demonstrating that, while they want to maintain Belarus under their sphere of influence, they don’t believe Lukashenko is necessary for that at the end of the day.

MAP SHOWING WHICH COUNTRIES SIDED WITH AND AGAINST LUKASHENKO,

BASED ON DATA FROM FREEDOM HOUSE AND VARIOUS NEWS SOURCES.77

On the flip side, there is an even greater number of countries that have criticized the actions of the Belarusian government or imposed sanctions upon them. In September, the European Union released a statement discrediting the election and supporting the protesters.78 Since then, the people included in the sanctions they have imposed include both Lukashenko and his son.79 The parliament of the European Union, as well as that of Lithuania (from where Tikhanovskaya has been operating), have also both declared that they believe Tikhanovskaya to be the democratically elected head of Belarus.80 These actions on the part of Europe are a move in the right direction to support a healthy democracy in Belarus in the face of a government that wants to maintain its grip on power at all costs. Other nations, including the United States, have made similar moves to denounce the election and impose sanctions upon the country.81 However, while these sorts of actions are a start in helping the Belarusian opposition, Tikhanovskaya has maintained that more must be done. In a December interview with Euronews, she stated, “ ‘Just imagine [that] 32,000 people are detained and only about 80 people are in the sanctions list.’ ” 82 For Lukashenko’s regime to face any serious threat, there needs to be more of a response than a slap on the wrist. The people of Belarus deserve justice and the opportunity to live in freedom, so if they aren’t able to achieve it alone, they need stronger assistance from abroad.

When hearing about the human rights crisis in Belarus, it’s hard not to draw parallels with other events that have occurred around the world during the same time period. While not directly connected with the protests in Belarus, many similar demonstrations represent a similar demand for justice across the globe. One example closely tied with that of Belarus is the protests that began in early 2021 in Russia. While these protests obviously had their own motive—these ones focused on the attempted murder and arrest of activist Alexei Navalny 83 —it cannot be doubted that the flames that lit them were stoked by the demonstrations occurring throughout Belarus. The world is more interconnected than ever, and people take inspiration from each other’s bravery, giving them the courage to stand up against injustice. Another parallel can be seen in the United States Capitol riots shortly before the inauguration of President Biden. In this, we see another group that is protesting because they believe the election results to be fraudulent. However, this event was different in that the protesters were being urged on by false information, as opposed to in Belarus, where the people were protesting against the false information.84 Through these events, we can find the importance that a fair democracy has for the people of a country, as well as how quickly it can be threatened. With this in mind, it is important that we support the fight for free and fair democratic institutions in Belarus and throughout the world. We must ensure that everyone receives fair treatment and a fair chance, keeping the power in the hands of the people.

Bibliography

AFP. “Belarus Police Detain Protesters, Prevent Opposition Rally.” Moscow Times, Mar. 27, 2021. https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2021/03/27/belarus-police-detain-protesters-prevent-opposition-rally-a73391.

Amnesty International. “Belarus: Impunity for Perpetrators of Torture Reinforces Need for International Justice.” Amnesty International, Jan. 27, 2021. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2021/01/belarus-impunity-for-perpetrators-of-torture-reinforces-need-for-international-justice/.

Aris, Ben. “Belarusian Police Introduce Colour-Coded Torture System for Detained Protesters.” bne Intellinews, Nov. 22, 2020. https://www.intellinews.com/belarusian-police-introduce-colour-coded-torture-system-for-detained-protesters-197150/?source=belarus.

Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project. “Lukashenko Versus Belarus: State Against the People.” Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, Sept. 24, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep26617.

Balmaceda, Margarita M. Living the High Life in Minsk: Russian Energy Rents, Domestic Populism and Belarus’ Impending Crisis High. Budapest: Central European University Press, 2014. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7829/j.ctt5hh00j.

Barros, George. “Belarus Warning Update: Belarusian Opposition Leader Directs Protesters to Employ Force against Lukashenko.” Institute for the Study of War, Nov. 11, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep27557.

BBC News. “Belarus Opposition Holds Mass Rally in Minsk Despite Ban.” BBC News, Aug. 23, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-53882062.

BBC News. “Belarus Opposition Threatens Lukashenko with Mass Strike.” BBC News, Oct. 13, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-54529828.

BBC News. “Belarus Protests: National Opposition Strike Gains Momentum.” BBC News, Oct. 26, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-54684753.

BBC News. “Belarus Protests: Police Authorised to Use Lethal Weapons,” BBC News, Oct. 12, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-54513568.

BelTA. “Foreign Leaders Congratulate Lukashenko on Re-Election.” BelTA, Aug. 10, 2020. https://eng.belta.by/politics/view/foreign-leaders-congratulate-lukashenko-on-re-election-132463-2020/.

BelTA. “Presidential Decree Signed to Declare 2021 Year of People's Unity in Belarus.” BelTA, Jan. 4, 2021. https://eng.belta.by/president/view/presidential-decree-signed-to-declare-2021-year-of-peoples-unity-in-belarus-136359-2021/.

Council of the European Union. “Belarus: Declaration by the High Representative on Behalf of the European Union on the So-Called ‘Inauguration’ of Aleksandr Lukashenko.” Council of European Union, Sept. 24, 2020. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2020/09/24/belarus-declaration-by-the-high-representative-on-behalf-of-the-european-union-on-the-so-called-inauguration-of-aleksandr-lukashenko/.

Council of the European Union. “EU Relations with Belarus.” Council of the European Union, Jan. 14, 2021. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/eastern-partnership/belarus/.

Daly, John C. K. “Russia’s Kavkaz 2020: International Participation and Regional Security Implications.” The Jamestown Foundation, Sept. 14, 2020. https://jamestown.org/program/russias-kavkaz-2020-international-participation-and-regional-security-implications/.

Davidzon, Vladislav. “Can Stalling Tactics Save the Wily Belarusian Dictator?” Atlantic Council, Jan. 20, 2021. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/can-stalling-tactics-save-the-wily-belarusian-dictator/.

Dixon, Robyn. “Belarus’s Lukashenko Jailed Election Rivals and Mocked Women as Unfit to Lead. Now One is Leading the Opposition.” Washington Post, July 23. 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/belarus-lukashenko-opposition-election/2020/07/23/86f231f6-c5ca-11ea-a825-8722004e4150_story.html.

Feifer, Gregory. “Belarus Will Be an Early Challenge for Biden.” Slate, Dec. 18, 2020. https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2020/12/biden-belarus-russian-putin.html.

Gerhart, Ann. “Election Results under Attack: Here Are the Facts.” Washington Post, Mar. 11, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/elections/interactive/2020/election-integrity/.

Human Rights Watch. “Belarus: Activists, Journalists Jailed as Election Looms.” Human Rights Watch, May 22, 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/05/22/belarus-activists-journalists-jailed-election-looms.

Human Rights Watch. “Belarus: Crackdown Escalates.” Human Rights Watch, Feb. 17, 2021. https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/02/17/belarus-crackdown-escalates.

Human Rights Watch. “Belarus: Events of 2020.” In World Report 2021. Human Rights Watch, 2021. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2021/country-chapters/belarus.

Human Rights Watch. “Belarus: Violence, Abuse in Response to Election Protests.” Human Rights Watch, Aug 11. 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/08/11/belarus-violence-abuse-response-election-protests.

Hurska, Alla. “What Is Belarusian Telegram Channel NEXTA?” The Jamestown Foundation, Sept. 23, 2020. https://jamestown.org/program/what-is-belarusian-telegram-channel-nexta/.

Ilyushina, Mary, Helen Regan, and Tara John. “Protests in Belarus as Disputed Early Election Results Give President Lukashenko an Overwhelming Victory.” CNN, Aug. 10, 2020. cnn.com/2020/08/10/europe/belarus-election-protests-lukashenko-intl-hnk/index.html.

Ilyushina, Mary, and Rob Picheta. “Belarus President Dismissed Covid-19 as 'Psychosis.' Now He Says He Caught It.” CNN, July 28, 2020. https://www.cnn.com/2020/07/28/europe/alexander-lukashenko-coronavirus-infection-intl/index.html.

Kim, Lucian. “Weeks After Disputed Election, Belarus President Is Secretly Inaugurated.” NPR, Sept. 24, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/09/24/916413744/weeks-after-disputed-election-belarus-president-is-secretly-inaugurated.

Krawatzek, Félix, and Gwendolyn Sasse. “Belarus Protests: Why People Have Been Taking to the Streets – New Data.” The Conversation, Feb. 4, 2021. https://theconversation.com/belarus-protests-why-people-have-been-taking-to-the-streets-new-data-154494.

Lubachko, Ivan S. “Historical Background.” In Belorussia: Under Soviet Rule, 1917–1957, 1–11. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 1972. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt130jm7w.4.

Moscow Times. “Russian National Guard to Partner with Belarus Police Amid Protests.” Moscow Times, Dec. 18, 2020. https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2020/12/18/russian-national-guard-to-partner-with-belarus-police-amid-protests-a72408.

Nechepurenko, Ivan. “Belarus Jails 2 Journalists for Covering Protests.” New York Times, Feb. 18, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/18/world/europe/belarus-protests-lukashenko.html.

Parrock, Jack. “Belarus Opposition Splits as Leaders Form New Parties.” Politico, Apr. 8, 2021. https://www.politico.eu/article/belarus-opposition-new-party-alexander-lukshenko-sviatlana-tikhanovskaya/.

Psaledakis, Daphne. “U.S. Expands Sanctions on Belarus over August Election, Crackdown on Protesters.” Reuters, Dec. 23, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-belarus-election-usa-sanctions/u-s-expands-sanctions-on-belarus-over-august-election-crackdown-on-protesters-idUSKBN28X1ZG.

Rainsford, Sarah. “Belarus: The Stay-at-Home Mum Challenging an Authoritarian President.” BBC News, July 31, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-53574014.

[REDACTED], through Telegram correspondence with the author, December 2020–February 2021.

Rettman, Andrew. “Exclusive: Lukashenko Plotted Murders in Germany.” EUobserver, Jan. 4, 2021. https://euobserver.com/foreign/150486.

Reuters Staff. “Belarus Police Detain over 100, Including Opposition Media Editors.” Reuters, Mar. 27, 2021. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-belarus-election-protests-idUSKBN2BJ0BE.

RFE/RL's Belarus Service. “Belarus Lawmakers Approve Amendments That Severely Restrict Civil Rights, Media.” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Apr. 9, 2021. https://www.rferl.org/a/belarus-lawmakers-approve-amendments-that-severely-restrict-civil-rights-media/31195872.html.

RFE/RL's Belarus Service. “Detained Belarusian Protesters Describe August Stay in Internment Camp.” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Jan. 29, 2021. https://www.rferl.org/a/31076165.html.

Roth, Andrew. “Belarus: Thousands Protest Against Death of Teacher in Police Custody.” The Guardian, Nov. 15, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/nov/15/belarus-thousands-protest-against-death-of-teacher-in-police-custody.

Seddon, Max, and Henry Foy. “Echoes of Belarus in Russia’s Navalny Protests.” Financial Times, Jan. 25, 2021. https://www.ft.com/content/fc83d419-adc2-4836-a921-28cb52d82fcf.

Shotter, James, and Max Seddon. “How Belarus’s Protesters Staged a Digital Revolution.” Financial Times, Feb. 25, 2021. https://www.ft.com/content/a68a1c28-fdd0-4800-9339-6ca1e81d456a.

Shraibman, Artyom. The House That Lukashenko Built: The Foundation, Evolution, and Future of the Belarusian Regime. Washington DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2018. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep16978.

Silva, Isabel. “Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya: EU Sanctions against Belarus Not Enough, Says Opposition Leader.” Euronews, Dec. 16, 2020. https://www.euronews.com/2020/12/16/sviatlana-tsikhanouskaya-eu-sanctions-against-belarus-not-enough-says-opposition-leader.

TASS. “Belarus' Lukashenko Says Only Election Can Decide the Future of His Presidency.” TASS, Jan. 5, 2021. https://tass.com/world/1242443.

TASS. “Over 33,000 Protesters Held in Belarus in 2020, Human Rights Activists Say.” TASS, Jan. 6, 2021. https://tass.com/world/1242519.

Tikhanovskaya, Svetlana. “Her Plan to Topple Europe’s Last Dictator.” New York Times, Sept. 23, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/video/opinion/100000007331325/belarus-tikhanovskaya-opposition-leader.html%0D.

U.S. Department of State. “Belarus 2019 Human Rights Report.” https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/BELARUS-2019-HUMAN-RIGHTS-REPORT.pdf.

UN News. “Belarus Human Rights Situation Deteriorating Further, Warns UN Rights Chief.” UN News, Feb. 25, 2021. https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/02/1085712.

Whitmore, Brian. “Belarus Presents the West with an Opportunity to Be on the Right Side of History.” Atlantic Council, Jan. 20, 2021. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/belarus-presents-the-west-with-an-opportunity-to-be-on-the-right-side-of-history/.

Image Sources

Girl with Flag

Kuzniatsou, Ilya. Girl with a White-Red-White Flag. Flickr, 2010. https://www.flickr.com/photos/54833413@N05/5160519867.

Lukashenko

Guchek, Maxim. Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko attends a meeting on the work of the economy in the current year in Minsk, Belarus, Monday, Dec. 7, 2020.. ABC News, n.d. https://s.abcnews.com/images/International/WireAP_e3f892e274b847c090e6787183b1589d_16x9_992.jpg0.

Sheleg, Sergei. Portrait of Alexander Lukashenko. The Sunday Times, n.d. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/imageserver/image/%2Fmethode%2Ftimes%2Fprod%2Fweb%2Fbin%2F824982ea-f5df-11ea-a46c-7a0b650e6a11.jpg?crop=2111%2C1187%2C443%2C30&resize=1180.

Lukashenko and Putin

Press Service of the President of Russia. Putin with Alexander Lukashenko 2015. kremlin.ru, 2015. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=40076025.

Police

Homoatrox. 2020 Belarusian protests — Minsk, 30 August. Wikimedia Commons, 2020. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=93684123.

Population Pyramid

PopulationPyramid.net. “Belarus.” PopulationPyramid.net, 2019. https://www.populationpyramid.net/belarus/.

Tikhanovskaya

Bundesministerium für europäische und internationale Angelegenheiten. Svetlana Tikhanovskaya in Vienna 1. Flickr, 2020. https://www.flickr.com/photos/minoritenplatz8/50437384937/.

Bundesministerium für europäische und internationale Angelegenheiten. Svetlana Tikhanovskaya in Vienna 2. Flickr, 2020. https://www.flickr.com/photos/minoritenplatz8/50437385087/.

World Map

Agencia Prensa Latina. “Rechazan en Cuba injerencia externa contra la soberanía de Belarús.” Escambray, Sept. 1, 2020. http://www.escambray.cu/2020/rechazan-en-cuba-injerencia-externa-contra-la-soberania-de-belarus/.

Belarus.by. “Syrian President Congratulates Lukashenko on Re-Election.” Belarus.by, Aug. 12, 2020. https://www.belarus.by/en/government/events/syrian-president-congratulates-lukashenko-on-re-election_i_0000117428.html.

BelTA. “Foreign Leaders Congratulate Lukashenko on Re-Election.” BelTA, Aug. 10, 2020. https://eng.belta.by/politics/view/foreign-leaders-congratulate-lukashenko-on-re-election-132463-2020/.

BelTA. “Nicaragua Officials Congratulate Lukashenko on Re-Election.” BelTA, Aug. 12, 2020. https://eng.belta.by/president/view/nicaragua-officials-congratulate-lukashenko-on-re-election-132509-2020/.

Council of the European Union. “Belarus: Declaration by the High Representative on Behalf of the European Union on the So-Called ‘Inauguration’ of Aleksandr Lukashenko.” Council of European Union, Sept. 24, 2020. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2020/09/24/belarus-declaration-by-the-high-representative-on-behalf-of-the-european-union-on-the-so-called-inauguration-of-aleksandr-lukashenko/.

Foreign & Commonwealth Office and The Rt Hon Dominic Raab MP. “Foreign Secretary Statement on Belarusian Presidential Elections.” Gov.uk, Aug. 17, 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/foreign-secretary-statement-on-belarusian-presidential-elections.

Freedom House. “Explore the Map.” Freedom House, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/explore-the-map?type=fiw&year=2021.

LithuaniaUN (@LithuaniaUNNY). “Joint Statement of co-chairs of UN GoF for PoJ on the situation in Belarus.” Twitter, Sept. 28, 2020. https://mobile.twitter.com/LithuaniaUNNY/status/1310610932687609856.

Ministry for Foreign Affairs. “Joint Statement of Nordic-Baltic Foreign Ministers on Recent Developments in Belarus.” Government Offices of Sweden, Aug. 11, 2020. https://www.government.se/statements/2020/08/joint-statement-of-nordic-baltic-foreign-ministers-on-recent-developments-in-belarus/.

Mohammed, Arshad, Matt Spetalnick, and Robin Emmott. “Exclusive: U.S., UK, Canada Plan Sanctions on Belarusians, Perhaps Friday,” Reuters, Sept. 24, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-belarus-election-sanctions-exclusive-idUSKCN26F2A5.

Oman News Agency. “HM The Sultan Congratulates Belarusian President.” Oman News Agency, Aug. 12, 2020. https://omannews.gov.om/NewsDescription/ArtMID/392//17355/HM-The-Sultan-Congratulates-Belarusian-President.

Reuters, Thomson. “Belarus Leader Lukashenko Says New Elections to Be Held Following Constitutional Referendum.” CBC, Aug. 17, 2020. https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/belarus-border-poland-eu-1.5689008.

Tomoyuki, Yoshida. “The Situation in the Republic of Belarus.” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, Aug. 19, 2020. https://www.mofa.go.jp/press/release/press4e_002881.html.

UN Web TV. “Urgent Debate on Belarus - 9th Meeting, 45th Regular Session Human Rights Council.” UN Web TV, Sept. 18, 2020. http://webtv.un.org/search/urgent-debate-on-belarus-9th-meeting-45th-regular-session-human-rights-council-/6192194462001/?term=2020-09-18&lan=English&cat=Meetings%2FEvents&sort=date#player.